BLOG

PILGRIMAGE | FEATURES | NEWS

April 27, 2021

1565: The Year of Amazing Discoveries

Fr. Arnel A. S. Dizon, OSA

The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) released its Pastoral Exhortation in 2012 with the subtitle “Looking Forward to Our Five Hundredth,” a pastoral reference to the quincentennial of Christianity’s introduction in the Philippines. CBCP designates the baptism event as the reckoning date of the commemoration. The Augustinians participate in the celebration of the faith with the 500 years of Santo Niño’s arrival which is believed to be the image presented by Magellan to Humabon’s consort after the occasion. An interval of forty-four years (1521-1565) supervened though on the Santo Niño narrative discourse until the arrival of the Legazpi-Urdaneta expedition in 1565, following several abortive attempts.

In the year 1565, two prodigious events marked the advent of Spanish expansionism in the Far East as categorized then —the discovery of Urdaneta’s route and finding of the Santo Niño icon. Spanish explorations to ‘the islands of the west’ (Las Islas del Poniente) had a singular objective: to discover a water route to the Moluccas, the source of the highly-coveted and expensive commodities in Europe. The lucrative spice trade lured the Spanish, Portuguese, British and Dutch commercial armadas to sail ahead to the Spice Islands of Moluccas. However, the pursuit for spices and other luxury goods by the major players of the time commanded a far higher value —the race for expanded power and uncontested supremacy. Hence, Spanish monarchy’s ultimate agenda focused on the creation of a global Spanish empire that covered geopolitical, economic, cultural, ecclesiastical and spiritual machineries.

In the year 1565, two prodigious events marked the advent of Spanish expansionism in the Far East as categorized then —the discovery of Urdaneta’s route and finding of the Santo Niño icon.

Fray Urdaneta discovered the return route across the vast Pacific.

Fray Urdaneta discovered the return route across the vast Pacific with finality and precision as instructed. He presented a material evidence of the unprecedented achievement: the chart of the newly discovered route of the voyage as authenticated by the Royal Mexican Audiencia, and the agreement of earliest textual sources in telling the same story. Perhaps the more convincing proof was the use of the chart and route in crossing the Pacific for a considerable period. Significantly, Urdaneta’s route established the shorter navigational transpacific route and connectivity.

Fray Urdaneta equipped himself with the three vital information needed for a successful and shorter return trip: sailing in the direction of the ocean currents and winds for a faster and safer trip; ships structural design that withstand the severe weather conditions; and sufficient food supplies good for months. And so, he delivered the royal undertaking.

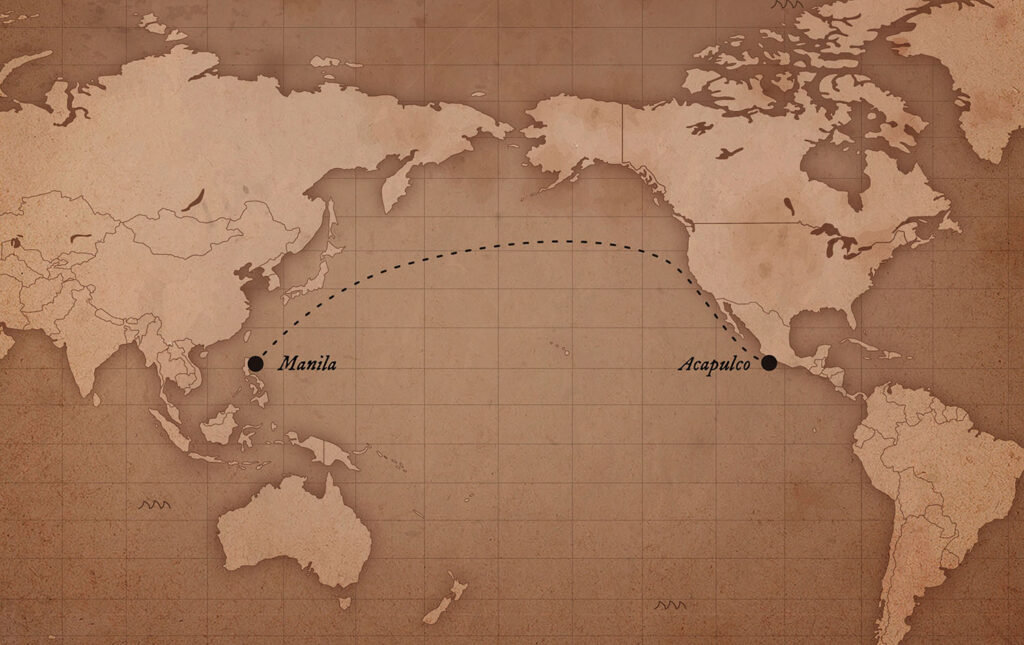

The magnitude of its impact encompassed intercontinental exchange, mobility and circulation of people, merchandise, ideas and learning between Asia and Europe, the Americas and even Africa. Symbolized by the galleon trade of the Manila-Acapulco route, commercial and cultural exchange ushered the development of maritime transportation and communication or correspondence, influenced migration, settlement, urbanization, labor and other ancillary services, occupations and industries that have evolved in diverse forms and expressions even to the present day.

At this juncture, the discourse transitions to sense-making to two acts or processes of discovery and finding. What is the significance of the discovery of Urdaneta’s route (la vuelta de Poniente) with Kaplag, the finding of the Santo Niño Image? It has to be remembered that Fray Urdaneta based the navigational chart of the transpacific route on his previous achievements and available data of the era; he employed his knowledge of the prevailing currents in the western Pacific and the Atlantic to return to Mexico. The success of the return route was highly dependent on the currents and prevalent winds at a specific period. This phenomenon explains the practical basis behind the choice of June 1 departure date from Cebu to avoid the monsoon rains and typhoon season that usually occurs from June to October. The foregoing realities do not, in any way, diminish the first-hand contributions and headship of Fray Urdaneta in the discovery of the route. He did not become the first to return from the islands of the west by pure chance. He was equipped with the essential knowledge and skills acquired through years of experience on the vast oceans and overseas. It is noteworthy to revisit the mandate of royal instruction no. 60: “to keep track of the route…and in general describing…everything that may be useful for future navigation.” The order considered the element of uncertainty of the outcome, yet it also reflected the envisioned project, that is, to maintain the Philippines as a springboard to the Moluccas and other islands, including the fabled ancient kingdoms of China and Japan. It was a double-purpose enterprise: for imperial-economic reasons and the proclamation of the Christian message of hope and redemption to newly explored lands.

Fray Urdaneta discovered the return route across the vast Pacific with finality and precision as instructed.

Clearly in faith and understanding, the finding of the Santo Niño Image was not a mere coincidence either. It was welcomed by the Legazpi-Urdaneta fleet as one of divine providence. Not long after, the event provided the crucial sign to establish with permanence the Spanish colonial outpost in the East. Hence, from the moment of the miraculous finding to the flourishing of works of evangelization, the sending and arrival of missionaries to the Philippines increasingly became regular, although the earliest period was characterized by instability, danger and resistance, scarcity of resources and personnel, and numerous other difficulties common in an emerging colonial settlement. Urdaneta’s route served as the galleon trade route wherein ships also ferried merchants, migrants, civil servants, soldiers, priests and missionaries from Mexico to Manila. The Spanish expeditions of Saavedra (1528) and Villalobos (1542) sailed as well from the Mexican port La Navidad. Sending of missionaries from the city port rather than of Spain was less expensive for the royal treasury.

Maintain the Philippines as a springboard to the Moluccas and other islands, including the fabled ancient kingdoms of China and Japan. It was a double-purpose enterprise: for imperial-economic reasons and the proclamation of the Christian message of hope and redemption to newly explored lands.

The Kaplag or finding of the image eventually started the veneration and popular devotion to the Holy Child. In due time, consequential and providential encounter formed the community of the baptized and faithful devotees through the religious zeal of the pioneering evangelizers in the islands. The Augustinians—equipped with the missionary experiences from Mexico and Peru—implemented a systematic evangelization, formal instruction and strategic Christianization in the expanding number of mission areas. Royal and ecclesiastical collaboration saw further increase of missionaries from other religious orders and some secular priests. Mutual and reciprocal influences ensued across the Pacific including the devotion to the Santo Niño de Cebu. In the 17th century, for example, the image of the Santo Niño de Cebu brought to Mexico (Juchitan) from the Philippines by a retired Spanish soldier attracted attention in the community for its tanned-color hue. Its provenance became a settled issue upon the intervention of the bishop of Puebla. In an unprecedented time, both discoveries opened the way for opportunities and possibilities, with the inconsistencies and misfortunes. The rallying point of the events designates that they transpired not by absolute luck but by one of divine intervention that desires to reveal the good news of an amazing God, journeying with his people in love and devotion. The celebrations on the quincentennial of the arrival of Christianity and the Santo Niño de Cebu icon attest to the grace-filled community of missionary disciples called to share the same faith in Christ in the Era of New Evangelization. God bless the Philippines and the whole world.

References:

Rodriguez, Isacio R., OSA. 1978. Historia de la Provincia Agustiniana del Smo. Nombre de Jesus de Filipinas, XIII. (HPAF, XIII). Manila: Arnoldus Press.

San Agustin, Gaspar de OSA. 1998. Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas, 1565-1615. First bilingual ed. Manila: San Agustin Museum.

The Christianization of the Philippines. 1965. Translated by Rafael Lopez, OSA and Alfonso Felix, Jr. Manila: Historical Conservation Society and University of San Agustin.