BLOG

PILGRIMAGE | FEATURES | NEWS

January 4, 2021

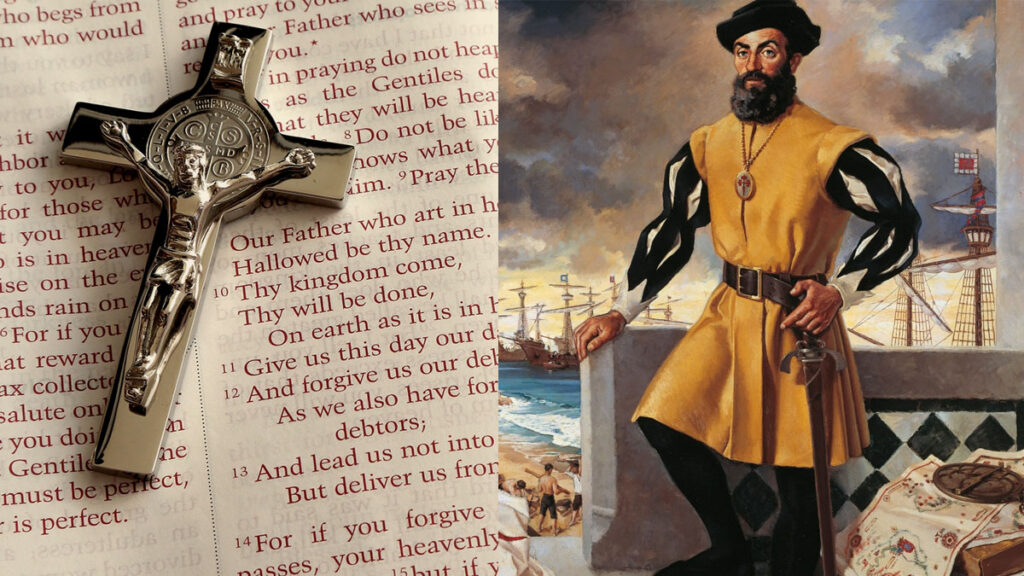

Ferdinand Magellan (Fernão Magalhães) and the Beginning of Christianity in the Philippines

Fr. Arnel Samson Dizon, OSA

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the abstract and full-text of the lecture delivered at the at the Sala Brazo of the Museum of São Roque on December 14, 2021, as a side event to the exhibition “O Menino Jesus de Cebu, um ícone da cultura e da história das Filipinas” (Santo Niño de Cebu: An Icon of Philippine culture and history). For more information about the lecture, you can read the article by clicking this link.

Abstract

The Santo Niño icon — among other imported merchandise set for sale, barter or as token — is the most enduring religious memory of the first encounter.

The quincentennial celebrations in the Philippines commemorate the edifying events of 1521, historically situated around the themes of victory and humanity. For its 2021 jubilee celebrations, the national Catholic hierarchy (Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines) focuses on ecclesial mission and renewed evangelization as it celebrates the 500 years of Christianity in the Philippines. The Augustinian Province of Santo Niño de Cebu in the Philippines anchors its festivities on the CBCP pastoral agenda, with highlight on the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the Santo Niño statuette in Cebu and its providential inspiration in the subsequent missionary endeavors. The introduction of Christianity on Philippine shore is closely associated with the coming of the empire-sponsored adventurers-cum-conquerors that brought along material and intangible elements of the Christian faith. The Santo Niño icon — among other imported merchandise set for sale, barter or as token — is the most enduring religious memory of the first encounter.

The ‘passing through’ of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in these islands on their way to the Moluccas made manifest the arrival of the faith and the Santo Niño icon, and the unintentional ‘discovery’ of the archipelago for the Spanish monarchy.

The brief presentation recalls and echoes the initial defining moments and views of the 500 years of Christianity that is basically grounded on the implantation of the seeds of faith, that brought about its developmental processes and implications in the life of the people as a nation and Church through the centuries. It is a celebration of the gift of faith although structurally framed with economic and political expansionist objective. In particular, the Philippine Church’s celebration is centered on journeying, growing, and deepening of the gift of faith introduced five hundred years ago. Ferdinand Magellan opened the path toward the establishment of the future colonial post in the far east by sailing westward and thus charting the circumnavigation route. He was instrumental as well in the introduction of the seed of Christianity in this part of the world. The ‘passing through’ of the Magellan-Elcano expedition in these islands on their way to the Moluccas made manifest the arrival of the faith and the Santo Niño icon, and the unintentional ‘discovery’ of the archipelago for the Spanish monarchy. Hence, the limited narrative explores the beginning and development of Christian faith with emphasis on fundamental Catholic representations and ceremonies.

Full Text

The 2021 Quincentennial Commemorations in the Philippines (NQC) celebrate the valor of a people characterized by the Victory at Mactan, and the Philippine part in the achievement of humanity in the circumnavigation of the globe. The NQC elevates the commemorations on a worldwide scale to highlight the rich heritage and flourishing civilization of the pre-colonial ancestors and forebears, institutionalized long before the encounters with foreign powers and entities from across the world. On the other hand, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) spearheads the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Introduction of Christianity in the Philippines. And the Augustinian Province of Santo Niño de Cebu in the Philippines anchors its festivities on the agenda of the CBCP, highlighting the 500th anniversary of the arrival of the image of Santo Niño in Cebu, and the intense devotion attributed to Holy Child’s guidance and inspiration.

International initiatives organized by agencies and organizations underscore the distinct Filipino way of representations and expressions. In collaboration with the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) and the Augustinian Province of Santo Niño de Cebu-Philippines, The Philippine Embassy of Lisbon participates in the commemorations through the mounting of Santo Nino de Cebu Exhibit at the Museu de Sao Roque, aptly tagged as Santo Niño de Cebu: An Icon of Philippine Culture and History. The exhibit illustrates the blending of culture and history, closely hinged by the religious component. The exhibit demonstrates how the gift and seed of Christian faith started in the archipelago of St. Lazarus, which came to be known as the Philippines.

The Armada de Maluco … was accidently and literally blown away from their course, propelled by powerful winds ended up in the Philippine islands.

The introduction of Christianity in the Philippines was marked by two (2) historical events stamped with essential Catholic signs and rituals. On both occasions, the Portuguese explorer-navigator Fernão de Magalhães came to be identified as Fernando de Magallanes who offered services and allegiance to the Spanish crown. Ferdinand Magellan prominently occupied a principal role as the captain general memorialized in human world history, although the Moluccas was the intended ultimate destination. The Armada de Maluco, in effect, was accidently and literally blown away from their course, propelled by powerful winds ended up in the Philippine islands. Even so, in a matter of forty-six (46) highly intense days (March 31-May 1) the Magellan-Elcano expedition took an abrupt, unfortunate end; nevertheless, able to proceed to the Moluccas and eventually return to home base. The definitive events while temporarily stationed in the Philippines included:

- The planting of the Holy Cross consecrated with the celebration of the First Easter Mass (31 March 1521).

- The giving of the Santo Niño Image associated with the celebration of the Sacrament of Baptism (14 April 1521).

The Planting of the Holy Cross

Magellan … intimated to the natives of the necessity of setting the cross up on the highest point of the mountain as a sacred symbol of worship and protection from harm each time they see it. upon reaching the island of cebu, magellan also planted the holy cross “at the center of the square” near the vicinity of the large port where they dropped anchor in compliance with the royal instruction. it is believed that the place is the present site of the kiosk of magellan’s cross located near the basilica minore del santo niño de cebu where the image was discovered by the legazpi-urdaneta in 1565, or forty-four (44) years after magellan’s arrival and death.

The planting of the Cross by Captain Fernando de Magallanes coincided with the celebration of the First Easter Mass (31 March 1521) in the Philippines (consistently confirmed by several panels of experts). The event signified the imperial claim and possession on ‘discovered’ territory for los Reyes Catolicos. The Catholic Monarch of Spain, King Charles I (r. 1516-1556) as noted by Pigafetta: Fernando de Magallanes “was charged and commanded” by the King “to set them up in all the places where he should go and travel.” Specifically, the planting of the cross, served as marker and advance notice to other Spanish-sponsored ships that allied explorers had subjugated the place. It was sort of a seal of allegiance that secured the natives’ safety from hostile forces. Magellan, moreover, intimated to the natives of the necessity of setting the cross up on the highest point of the mountain as a sacred symbol of worship and protection from harm each time they see it. Upon reaching the island of Cebu, Magellan also planted the Holy Cross “at the center of the square” near the vicinity of the large port where they dropped anchor in compliance with the royal instruction. It is believed that the place is the present site of the Kiosk of Magellan’s Cross located near the Basilica Minore del Santo Niño de Cebu where the image was discovered by the Legazpi-Urdaneta in 1565, or forty-four (44) years after Magellan’s arrival and death.

They should not be forced to accept the sacrament out of fear but out of good will and love of God, the captain convincingly clarified….Pigafetta noted that “all cried out together with one voice” of their free choice to be baptized christians. The captain and natives led by the chieftain concluded the perpetual peace pact with a mutual promise, a fraternal embrace, and tears of joy.

The reckoning date of the quincentennial commemoration of Christianity in the Philippines concurred on the 500th anniversary of the baptism in Cebu (14 April 1521-2021) which happened in succession which gained around eight hundred (800) new Christians. The following explorations brought them on the neighboring islands. Magellan-Elcano expedition entered the strait leading to the best trading port of Cebu to find necessary provisions. As a standard protocol, Pigafetta narrates that the chieftain was informed through the interpreter that Magellan represented the greatest king, and that by his command he was tasked to discover the west-ward route to the Moluccas, the Spice Islands. In less than a time after straightforward talks and negotiations (and subtle threats), a peace and friendship pact commenced a cordial relation between Magellan and the chieftain of Cebu, Rajah Humabon. The captain convincingly shared some Christian teachings and practices “to induce them to become Christians” and indeed, were moved to assent and “begged the captain to leave them two men” that can further instruct them on matters of the new faith. This is viewed as a turning point for Magellan from being a ‘mercenary’ to a ‘missionary.’ Yet the Mactan incident revealed a momentary state of perspective. Magellan responded to the appeal with a promise to fulfill later and offered instead the voluntary reception of baptism. They should not be forced to accept the sacrament out of fear but out of good will and love of God, the captain convincingly clarified. With added security premium once baptized, Pigafetta noted that “all cried out together with one voice” of their free choice to be baptized Christians. The captain and natives led by the chieftain concluded the perpetual peace pact with a mutual promise, a fraternal embrace, and tears of joy.

The Giving of the Santo Niño Image

Humamay, the queen-consort named Joanna (Juana) after the emperor’s mother…requested the wooden image “to put in place of the idols,” reverently enshrined in her dwelling place. Magellan subsequently gave the wooden image of the Holy Child to replace her gods.

The local chieftain who promised to be a Christian prepared the forthcoming baptism with a platform installed at the central square. The celebration of the Sacrament of Baptism happened on a Sunday morning of 14 April 1521. Magellan “initiated the rajah into the faith of Jesus Christ” including the encouragement of exterminating all the idols in his authority as clear indication of a faithfulness to one’s identity as Christian. The gesture portrayed Magellan giving basic catechetical instructions revealing his knowledge of the same faith. The local chieftain and his subjects agreed to the captain’s persuasion. He was named Charles (Carlos) in honor of Emperor Charles and fifty men were baptized with him. In the afternoon of the same day, forty women were Christianized with Humamay, the queen-consort named Joanna (Juana) after the emperor’s mother. Juana, Pigafetta remarked, requested the wooden image “to put in place of the idols,” reverently enshrined in her dwelling place. Magellan subsequently gave the wooden image of the Holy Child to replace her gods. They were locally known as anitos, the deified ancestor and nature spirits. The replacement and destruction of the traditional images however took for some time to accomplish.

It took forty-four long years of interregnum until the Santo Niño icon resurfaced in time with the rediscovery by the Legazpi-Urdaneta expedition in 1565 that finally launched the formal and systematic evangelization of the Philippines. The Order of Saint Augustine became the pioneering missionaries in the islands and the caretakers of the Santo Nino of Cebu up to this present day.

With the untimely demise of Magellan on Mactan, the progress of Christian instruction of the baptized locals was abruptly terminated. Sebastian Elcano assumed the leadership of the remaining contingent and successfully completed the perilous voyage. It took forty-four long years of interregnum until the Santo Niño icon resurfaced in time with the rediscovery by the Legazpi-Urdaneta expedition in 1565 that finally launched the formal and systematic evangelization of the Philippines. The Order of Saint Augustine became the pioneering missionaries in the islands and the caretakers of the Santo Nino of Cebu up to this present day. In honor of Ferdinand Magellan, the street that separates the Basilica del Santo Niño complex and the Kiosk of Magellan’s Cross in Plaza Sugbo (Cebu) was named after him. But due to environmental effect on structural integrity of heritage structures, heritage district zoning and the economic development on the area, Magallanes Street fronting the basilica and plaza complex was closed to vehicular traffic.

Select Bibliography:

Gerona, Danilo Madrid. (2016). Ferdinand Magellan: The Armada de Maluco and he European Discovery of the Philippines. Spanish Galleon Publishing Philippines.

Pigafetta, Antonio. (1969). Magellan’s Voyage. A narrative account of the First Circumnavigation. Vol. I. Translated and edited by R. A. Skelton from the manuscript in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Oliveira, Fernando. (2002). The Voyage of Ferdinand Magellan (Viagem de Fernão Magalhães). Translated from the original Portuguese manuscript in the University Library of Leiden. P.G.H. Schreurs, MSC. Manila: National Historical Institute.

San Agustin, Gaspar. (1998). Conquest of the Philippine Islands (1565-1615). First bilingual ed. Translated by L.A. Mañeru. Manila: San Agustin Museum.

Valles, Romulo G. For the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines. Pastoral Letter Celebrating the 500th Year of Christianity in the Philippines. 23 March 2021. Manila: cbcpnews.net.